I suppose all parents have those first moments of recognition; the sudden realization that the world has pushed itself inside your child’s innocence, the bittersweet rush of comprehension that s/he will never be quite the same again.

Having a child with disabilities creates a different trajectory. Timelines are unpredictable. Those milestones that mark the development of most children may never appear. They may show up in different forms, or make an appearance years later than what is considered typical.

In my 28 years of parenting a child who carries several heavy labels, autism chief among them, I’ve had the pleasure of knowing many individuals who also shoulder that diagnosis, and they are just that–individuals. Though there are common clues that might alert the uninitiated, there is no absolute list of characteristics that defines them all. One of the more common hallmarks, though, is what the world calls literal thinking.

There are so many ways that language can be bent to suit our needs for expression. Idioms, metaphors, hyperboles and analogies come easily to those of us who have natural fluencies, but these rather abstract concepts can be baffling for many folks on the autism spectrum.

Bink has a volunteer job at a wonderful store in a town nearby that sells books and toys. This was a giant leap for her. Though she adores colorful toys and fun activities geared towards a much younger crowd, the things that go along with having a job—taking and following direction, limiting breaks, staying with the task at hand, and persevering through non-preferred duties——are real hurdles for her. She has done well, though, gradually building up to a few hours there. Her one-on-one staff, S, is a patient, gentle woman who brings her own parenting experience along with her. Bink loves her and I frequently thank the stars above for the gift of her on our doorstep each Tuesday. The owner and staff at the store are also incredible. They consistently come up with a list of things for Bink to do, ensuring the variety she so craves.

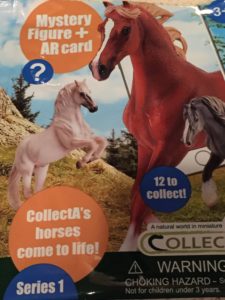

One Tuesday at the store, Bink spotted a collection of small plastic packages with images of horses on the front. She used to have weekly horseback riding lessons, but that was snuffed out when Covid arrived, and we’ve no idea when this marvelous activity will return. She took note of the horses, and a few days later she mentioned the toy in her very typical way.

Bink: I wanted that thing.

Me: What thing?

B: The thing at the toy store.

Me: What was it?

B: The magical thing.

Me: You have money you have earned from your chores. Do you know if you have enough to buy the magical thing?

Bink: I don’t know.

Me: Well, when you go there next week, maybe S can help you figure out if you have enough money saved to buy it. We can put some of your money in your purse so you can pay for it.

Bink: I am not supposed to play with the toys.

Me: Well, you can look for it when you are finished with your work for the day, and buy it if you have enough money.

Bink: I am at work.

Me: OK, well maybe we can make a separate trip and look for the toy.

Bink: OK.

A few days passed. We had the welcome opportunity to have a caregiver come for a few hours on the weekend. Bink loves to go out places. Walks, stores, anywhere. Since Covid, the options are limited. The toy store does have a careful health protocol, and she is comfortable there, so we agreed that would be a good destination. I made sure she had some money in her purse, and off they went.

A few hours later, she returned with a small plastic package containing that magical thing. It was a little horse figurine made of plastic. I helped her open it, and she trundled into the next room with it. A short time later, I saw the empty wrapping in the trash. She’d put the little horse in my home office, which is where she deposits things that she wants to get rid of.

Me: You don’t like the horse?

B: It doesn’t work.

Me: Well, it’s just a little statue. It’s not meant to move or anything.

B: It doesn’t work.

Curious, I pulled the wrapping out of the trash. The words on the plastic wrapper were quite clear. “Blankety-blank brand horses come to life!” Aha! A major clue.

Me: Honey, did you think the horse would move?

B: I wanted to see it come alive.

The words that came to mind immediately? Deceptive advertising! Those words slipped out against my better judgement, so I tried to explain the concept, but my sentences twirled off into little question marks in the air around my daughter’s ears. So I did what I often do. I grabbed one of my handy responses, the kind that often feel like a feeble excuse for the shortcomings of the mainstream majority:

Things don’t always make sense. People are confusing.

Sometimes it feels like hefty chunks of days are spent struggling to explain to my clear-eyed girl that the world is full of people who don’t say what they mean and often don’t mean what they say. That sometimes it is considered OK to say and write things that aren’t true, especially if it makes people feel better or makes them want to buy something. That many things we’ve come to accept as perfectly fine, aren’t fine at all. When I view events and people from Bink’s perspective, which I often do, the myriad contradictions and unnecessary noise seem quite nonsensical. My head starts to feel like a spinning top, and I want to crawl deep inside myself where it is much quieter, and stay there a long while. Literally.

Hope is a brief scatter of diamonds