The Names Project, AIDS Memorial Quilt

Have you ever dreamed someone alive again, someone long dead, whose memory visits rarely? Have you seen the watery shine of his eyes, smelled the shampoo lingering in her hair?

I’m talking about a dream SO real, you feel like you’ve stepped over the line between this reality and another, but your feet are firmly planted on some kind of hard surface. It feels like anything but dream state.

Recently, an old friend came to me this way, under cover of darkness. I could clearly hear his even, slightly nasal voice. I could reach out and touch that black jacket he always wore. It opened a thirty five year old box of memories, and I’ve been pulling them out and examining them from new angles, with older eyes.

In the early eighties I worked for a time at a health food store in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Thirty year old Barry was one of my bosses there. He was a slight, redheaded, soft-spoken guy whose flat affect belied a wicked sense of humor that took me some months to appreciate. Over time I became friendly with Barry outside of work, and when he moved to my Boston neighborhood, we’d get together at night sometimes, and walk and talk.

Barry loved the wind. We used to enjoy walking across the Longfellow Bridge that connects Cambridge to Beacon Hill. There, breezes seemed common, and sometimes they escalated to whipping gusts that would blow our jackets open and leave us unsteadily defending our relationship with gravity. “Can you feel it?” he’d say, “ Can you feel the power and the energy in the wind?”

I left the health food store for a higher paying job after about a year, but Barry and I stayed in touch. My tiny basement apartment on Irving Street was a short walk from his favorite bar, Sporters. Sometimes he’d stop in on his way there. Self-defined as happily wanton , he was always excited and hopeful for a rendezvous. This was the beginning of the eighties, and Barry was gay.

I’m not sure when he began to get sick. One evening we planned to bridge walk, but he called and said he had the flu. After that, there were sore throats, and later, an odd rash. Though he still frequented his favorite bars, he was often tired. He began to stop by less. I felt like he was avoiding me.

The early reckoning with what was being called Gay Related Immune Deficiency (or GRID) was in the news. Stories and guesses, educated and not so, swirled in the air. People were scared. Barry told me his former roommate had declared he’d remain celibate until someone found a cure to what some were calling the The Gay Plague. “I can’t do that,” Barry told me, “but I’m trying to be safe.”

John, a friend his, died. I didn’t know if they had been lovers, and I didn’t ask. On what would turn out to be our last walk across the Longfellow, we stopped in the middle and he said “ Can you feel it? It’s John. I think he’s in the wind.”

I suspect Barry was in denial, and he stayed there as long as he could. One night I awoke to a knock on my window. When he came in, he looked as thin and pale as I’d ever seen him. I didn’t address it. I think I was afraid of saying the wrong thing. Truthfully, I was afraid in general. Nobody was certain what was causing this mysterious illness, or exactly how it was spread. He sat down on the floor of my tiny, sparsely furnished studio apartment. I didn’t want to do anything to make my friend feel shunned, yet I was a floor sitter myself, and that day I stayed perched on my futon.

I might have offered some water or a snack. I don’t recall those details, but I remember the way he looked at me. I remember thinking that his serious expression wasn’t hiding one bit of humor anymore. “I’m having night sweats.”, he said at last. I wasn’t versed in the various symptoms that were possible with GRID infection, but I sensed a finality in his words.

Barry went back to his suburban childhood home shortly after that, and took up an uneasy residence in his old bedroom. His parents ministered to him. I visited there twice. The first time, he called me over to his bed and furtively handed me the key to his Boston apartment. He wanted me to get his stuff out. I knew he meant anything that his parents might view as incriminating. They did not acknowledge his sexual orientation, preferring to tell everyone that he was simply shy around women. I felt rather heartsick for him, imagining that a loving and complete acceptance from his parents might have meant the world to him then.

“Of course I will.” I wanted to be reassuring and nonchalant and as cool as the wind Barry loved. I wanted to be in that minority that seemed to stay grounded in the face of this frightening collection of symptoms that was taking lives with no regard to age, race or class. I wanted to be part of his support system, without question or judgment. I donned rubber gloves in his apartment, though, and threw them away afterwards with the rest of the things I gathered. As I dumped the bag in a trash bin, I felt a small, creeping shame.

A few weeks later his family finished clearing out the apartment. Next time I visited him in his childhood room, I brought the three packages of Sunny Doodles frosted cupcakes he’d requested. He’d been pretty vigilant about his healthy diet and supplement regimen for as long as I’d known him. It seemed he was giving himself permission to let go and enjoy what he could, while he could.

Shortly after that visit, Barry went into the hospital. I saw him there only once, when he was conscious but just hanging on. He had tubes in his arms and an oxygen mask on his face. AIDS had replaced GRID as the name for the devastating collection of symptoms showing up in increasing numbers, especially in gay men and some drug addicts. It was still fairly early in the epidemic, though, and there were elaborate precautions taken by hospital staff. Some visitors wore masks. I touched his hand but kept some distance from him, and then chastised myself for being fearful. His only sibling was there, and she took me aside at one point and thanked me for coming. She also bemoaned the fact that her parents still refused to acknowledge what was really happening. Again, my heart broke a little—for him, for her, and for a world that stoked such prejudice and erected sad barriers between people.

At Barry’s wake, his parents were impeccably dressed and stoic in their posture, trying to greet each mourner who filed past the closed casket. His sister was weeping in short bursts. After people paid their respects to the family, they gathered in small groups in the corners. I recognized some of them as Barry’s friends that used to come into the store. There was a group of men in Hawaiian shirts, laughing and talking as they shared memories. I guessed there was some special meaning to the shirts, and I also wondered if any of those men had been his partners.

There were some people from the health food store, and a High School teacher who remembered Barry from fifteen years earlier. I watched Barry’s sister leave her parents to move deliberately around the room and greet each person. She took the hands of many people in her own, and looked into their eyes. When she approached me she squeezed both my hands and asked how I was doing. Shocked at her selflessness and her concern for me, I remember fumbling over my words, trying to find the right ones and feeling an acute lack of maturity and grace.

Barry popped into my mind here and there for some years, certainly as AIDS garnered more attention. Precautions were outlined for everyone as the master immune compromiser began to show up in more segments of the population. The news told us that researchers were working feverishly to find ways to wipe out the virus and to mitigate symptoms in those already infected. I knew by then that I could never have acquired the disease with casual contact, and I held on to regret for my former fear and doubts. When the wind kicked up and tugged at my jacket and whipped my hair around, I tried to feel Barry in the rush of energy, but he never came.

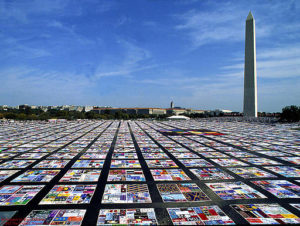

After awhile, memories of him and that time faded a bit. Several years later I ran into an old health food store co-worker on the street in the Boston financial district where I was working. He told me that he and several friends approached Barry’s parents and told them they were making a commemorative patch for the Names Project AIDS Memorial Quilt in Barry’s name. His parents wanted nothing to do with it and even asked them NOT to put their son’s name on it.* My heart cracked a little more that day.

I am not sure why Barry visited me in a dream. Perhaps enough time has elapsed that I can now offer my young self some compassion for having a level of fear during that time. Maybe, it’s the right time to honor the memory of a young man who loved the wind, a gentle soul who left us far too soon.

–Melinda Coppola

*Barry’s name IS on the quilt, in cotton candy pink letters against a pale gray background. I think he would have approved.

Beautiful, Melinda. At the time you speak of, my youngest son was a little boy in first or second grade. I vividly remember him asking me if he would get AIDS, and having to explain why he, a small child (who didn’t have sex or use intravenous drugs or get blood transfusions), wasn’t at risk in terms he could understand. My heart cracked a little that day too.

Thanks, Denise, for the comment. I’m grateful we’ve come so far, but there is still much to do.

Sad and beautiful.

Indeed. Thanks, Lianna.